Carbohydrate Use Disorder?

John (name changed to preserve privacy) was no stranger to the clinic. For years he had been told if he didn’t modify his lifestyle he would be at high risk for a diabetic amputation.

Diabetes attacks a person’s limbs in two primary ways: peripheral artery disease (PAD) and diabetic neuropathy. Neither of these diseases is a fast killer.

PAD starves your legs of blood, making them more likely to get ulcers and infections. Neuropathy damages the nerves, making it such that you won’t feel pain from an ulcer or walking on a sharp rock.

Diabetic amputations usually start off small. A toe here, a toe there. Then maybe half a foot.

They are NOT the result of some sudden occurrence that immediately requires a catastrophic measure.

John became one of Laura’s patients during her first year of residency. By then he had lost his entire left foot.

Laura spent time with both John and his wife, explaining that the insulin wasn’t doing enough. If John did not change his diet he would surely lose more of his left leg and his right leg too.

John would nod respectfully, it was clear that he understood. His wife would shrug her shoulders and say: “But it’s what he likes to eat? I have to give him what he wants”.

There were numerous amputations over the subsequent three years. By the time she finished her residency John had lost both legs past the knee and was confined to a wheelchair.

In the United States alone there are around 200,000 amputations performed annually. 130,000 of them are performed on people with diabetes.

As of 2018: Throughout the world, it is estimated that every 30 seconds a leg is amputated. And 85% of these amputations were the result of a diabetic foot ulcer.”

Begs the question: if someone is willing to trade their limbs for a bowl of pasta and piece of cake - is it fair to say addiction is present?

Addiction is an increasingly loaded term.

The NIH defines drug addiction as: a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences. It is considered a brain disorder, because it involves functional changes to brain circuits involved in reward, stress, and self-control.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine defines addiction as: a treatable, chronic medical disease involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, the environment, and an individual’s life experiences. People with addiction use substances or engage in behaviors that become compulsive and often continue despite harmful consequences.

For purposes of insurance reimbursement the definition is not condensable to sentence format, rather it is a list of behaviors one must engage in, determined by the American Psychiatric Association (more below).

Across all definitions is a theme: addiction is anything that leads to recurring suboptimal behavior.

The APA releases something called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM for short). The DSM manual is currently in its 5th edition, and is used in establishing the (psychiatric) ICD codes the medical system runs on.

In the rest of this post we’re going to look at alcohol use disorder (AUD for short) and the criteria used to diagnose it. Then we’ll (mostly) leave it to you to decide whether food - and specifically carbohydrates - deserve their own Use Disorder section in the DSM manual. First a quick snippet from the NIH:

AUD is estimated to cost more than $249 billion per year just in the United States. Worse still is the human toll, which includes 88,000 deaths per year and far more pain and suffering besides. The abuse of alcohol and other substances are considered to be psychiatric disorders.

Alcohol’s problems have been recognized by physicians since at least the late 1700s, though certainly any savvy observer would have been able to discern problematic patterns surrounding alcohol consumption from the time the first fermented fruits were imbibed. The 1930s saw the formation of Alcoholics Anonymous, and by 1940 “alcoholism” had officially become a disease.

It is important to recognize AUD and other forms of addiction as diseases because that recognition is a pre-requisite for getting insurance companies to cover the costs of rehabilitation and treatment. Further, with the benefit of hindsight we now know that such official designations also do wonders for lessening societal stigmas.

According to the DSM-5 Criteria, in order to be diagnosed with AUD you must have at least two of the symptoms listed below. The severity of the disease is further broken down into three tiers:

· Mild: The presence of 2 to 3 symptoms

· Moderate: The presence of 4 to 5 symptoms

· Severe: The presence of 6 or more symptoms

The bold/italicized text is our adapted commentary.

Symptom List. In the past year, have you:

1. Had times when you ended up drinking more, or longer, than you intended? Eaten more, or for longer than you intended?

2. More than once wanted to cut down or stop drinking, or tried to, but couldn’t? Wanted to cut down or stop eating, but couldn’t?

3. Spent a lot of time drinking? Or being sick or getting over other aftereffects? Spent a lot of time eating, snacked frequently, or felt sick after having eaten too much?

4. Wanted a drink so badly you couldn’t think of anything else? Wanted to eat so badly you couldn’t think of anything else?

5. Found that drinking – or being sick from drinking – often interfered with taking care of your home or family? Or caused job troubles? Or school problems?

6. Continued to drink even though it was causing trouble with your family or friends?

7. Given up or cut back on activities that were important or interesting to you, or gave you pleasure, in order to drink?

The connection to #5/6/7 may be less obvious because these impacts are not experienced acutely. But consider the case of our patient John from above. He sacrificed his ability to walk in order to keep eating the foods he liked. That easily meets each of the above.

8. More than once gotten into situations while or after drinking that increased your chances of getting hurt (such as driving, swimming, using machinery, walking in a dangerous area, or having unsafe sex)? This one is unique to acutely mind-altering substances.

9. Continued to drink even though it was making you feel depressed or anxious or adding to another health problem? Or after having had a memory blackout? Continued to eat even though it was making you feel depressed or anxious or adding to another health problem? Obesity is a disease well known to cause or exacerbate many health problems.

10. Had to drink much more than you once did to get the effect you want? Or found that your usual number of drinks had much less effect than before? Had to eat more than you once did to get the effect you want? Or found that your usual meal size filled you less than before? This one deserves extra space (see below #3).

11. Found that when the effects of alcohol were wearing off, you had withdrawal symptoms, such as trouble sleeping, shakiness, restlessness, nausea, sweating, a racing heart, or a seizure? Or sensed things that were not there? Found that when you had recently tried to cut out carbohydrates or were hungry you had symptoms like trouble sleeping, shakiness, irritability, restlessness…

You might have noticed that the title of this post is Carbohydrate Use Disorder, not Food Use Disorder. We’ll close this post by explaining the three reasons why:

Observation

Processed food dynamics

Insulin/biochemistry & brain scans

Observation. You have probably observed this in your own life. A friend of ours recently commented that he had seen more people succeed at quitting smoking than quitting sugar. This jived with our own experiences. Just an anecdote…

Laura and Matt first became interested in metabolic health during their final years of medical school. Ever since they’ve made a point of staying on top of the latest studies and connecting with the best people in the medical weight loss and metabolic health fields.

Matt is the chair of the Resource Committee for the Society of Metabolic Health Practitioners (SMHP). His role is to curate resources on nutrition and metabolic health, and then to work with medical students, residencies and clinicians to integrate them into their educational programs and daily practices. Laura sits on the board of the SMHP.

The point is, the anecdotes we are exposed to through our daily lives and other professional interests represent a large and growing pool of evidence, and it all points in one direction. Carbs are different.

We have yet to run into someone who developed obesity on a low-carb diet, though many individuals living with obesity can successfully maintain a low-fat diet.

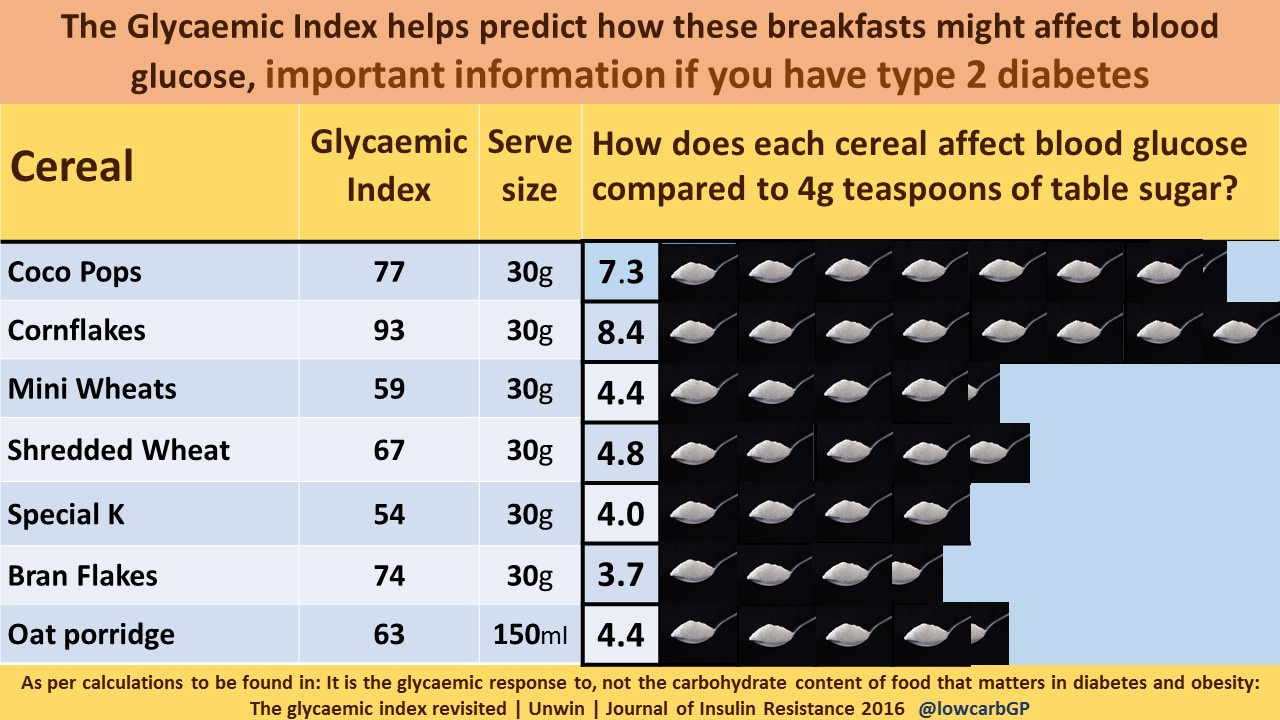

Processed food dynamics. Look at the following image from Dr. David Unwin:

Processed foods are capable of incorporating (and hence delivering to you when you eat them) higher densities of sugar than occur naturally. Note that 30g is a standard serving size but most people eat more than that when they pour a bowl of cereal.

Think about how easy it is to down a 30oz Coke (standard large size), which has 350 calories - all of them from sugar…

Quick aside: Because your resting metabolic rate increases as you gain weight, it usually requires more calories to put on new pounds than it did to put on the pounds that came before. This goes back to #10 above, needing to eat more to get the same “effect”.

Insulin/biochemistry & brain scans. A really exciting study was recently conducted by researchers at Harvard Medical school and published in the Journal of Nutrition. It was led by Drs. Laura Holsen and David Ludwig, and we also want to give a shout out to Diet Doctor for their great interview with Dr. Holsen that can be found here.

Dr. Holsen and her team took 72 overweight volunteers and randomized them into groups with the following diets:

60% carbs, 20% fat, 20% protein

40% carbs, 40% fat, and 20% protein

20% carbs, 60% fat, and 20% protein

For the entire study patients ONLY ate food that was provided so macronutrient intake could be precisely administered.

Volunteers then underwent fasting brain MRI scans to measure what is called regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) in brain regions involved in hunger and reward. This scan was followed by another scan four hours after eating their first meal of the day.

Consistent with their hypothesis, rCBF was 43% higher in adults on the high carb diet after a meal and 51% higher during the fasting state as compared to adults on the low carb diet. If you believe that the body reacts differently to carbohydrates vs. fat as we do (remember, protein was held constant) then this is what you would expect to see.

But, maybe even more interesting than the primary finding was the connection discovered between insulin sensitivity and brain response within the high carbohydrate group.

The pancreas of people living with type 2 diabetes still produces insulin, but their bodies don’t respond as strongly to it as they should. This is called insulin resistance, and the body’s default response to insulin resistance is to produce more insulin.

With that in mind, here’s the key quote from the study: “Those with higher insulin secretion after a glucose load had a lower activity level in the reward region compared to those who had lower insulin secretion”.

This means that people with lower insulin sensitivity are literally building up a tolerance for carbohydrates. Their body is providing less reward per calorie of carbohydrates than the bodies of people who have higher (healthier) insulin sensitivity.

This is analogous to the reward deficit model of addiction, which explains why those with addiction need to take increasingly large doses to get the same amount of pleasure.

There is no doubt that General Mills and other companies who like to claim their products are "Heart Healthy” will put up a vicious fight to defend carbohydrates, but the evidence is building.

It’s only a matter of time before Carbohydrate Use Disorder becomes a part of the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM manual.